The blues had a baby, and they named him Joe Bonamassa .

At the ripe young age of 12, he opened for B.B. King, then he came under the tutelage of the late blues/jazz impresario Danny Gatton as a teenager, won scores of Best Guitarist accolades all along the way, and has since stood toe to toe with the likes of Eric Clapton and Aerosmith's Brad Whitford, and formed the Black Country Communion superquartet with onetime Deep Purple bassist Glenn Hughes, drum legacy/phenom Jason Bonham, and keyboard whiz Derek Sherinian. (No slacker, he.)

“I think that was the most organic version of 1s and 0s.”

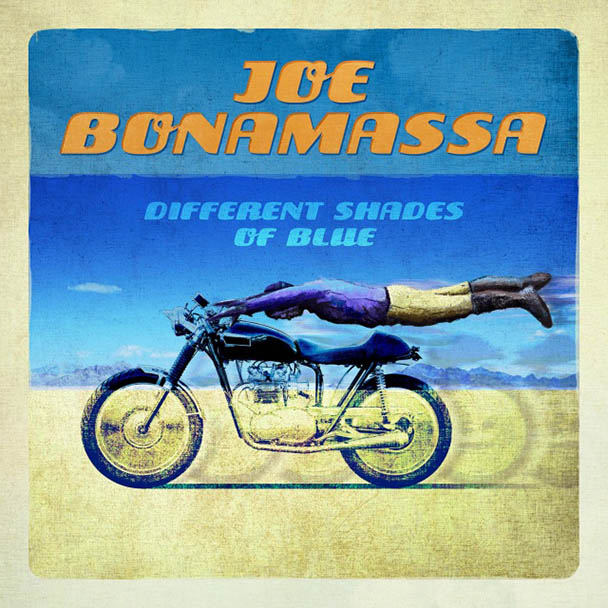

Bonamassa’s latest album, Different Shades of Blue, out now on his own custom J&R Adventures label, debuted at number eight on the main Billboard albums chart, and it shows the widening of his aural palate. In addition to the seriously smoking guitar solos on gutbucket cuts like “Love Ain’t a Love Song” and “Get Back My Tomorrow,” Bonamassa bobs and weaves with a tight horn section on “Living on the Moon” and “Trouble Town,” and interlaces beautifully with a churchified organ and uplifting string section on the album’s touching closer, “So, What Would I Do.”

Bonamassa, 37, sat down with Digital Trends in New York recently to discuss his digital production philosophy, his favorite gear, honesty in the studio, and the lost art of sequencing. “I always say the downfall of my career would be if I had a radio hit,” he jokes. No need to worry about that - smokin’ Joe B is here to stay.

Digital Trends: Let’s get right to it. 16-bit, or 24-bit?

Joe Bonamassa: On a CD, I like 16.

Because...?

I like early digital stuff. I think that was the most organic version of 1s and 0s. In my world, for guitar, the early digital delays, reverbs, and effects - like the TC 2290 [digital delay/multi-effects processor] - were all 16-bit, and there’s a real beauty to that. The more the bit rate goes up, and the more the resolution and fidelity goes up, the more the human ear “hears,” and the less it impacts the soul.

So it’s a “feel” thing for you, to some degree. Is hi-res audio too clinical?

We’re dealing in frequencies that birds and whales communicate in. If you put on a vinyl record, through an analog Pioneer player and a couple of Bose 901s, the frequency band doesn’t get below 250 Hz. You might get above 3 to 5 K - and that’s midrange, where it feels very organic to me. I don’t feel that better fidelity means better sound - at least to the listening ear. Maybe it does on paper.

Certain artists and producers feel the bit rate is more important than the sampling rate, so what do you think about 96kHz?

It was never in the music to begin with. Those frequencies weren’t replicated by instruments, you know what I mean? When ProTools went to 96, then ProTools was real. The original ProTools sounded harsh and terrible - those old Mitsubishi reel-to-reels were 16-bit or 24-bit, and they sounded like shit. They would just ram 2K into anything. You couldn’t get 2K out quick enough. So I think 96 is the magic number for ProTools in our world.

As far as home stereo listening goes, I’m analog all the way. I really love that early solid state - McIntosh 2205 [power amplifiers], 100 watts a side. Even on a CD, the band sounds like it’s in the room.

That’s one of my favorite things - listening to music where you can really hear everyone playing together in the same room, at whatever volume.

“I don’t feel that better fidelity means better sound.”

You want to know a really wacky fact about me? Freud would have a field day with this. For someone who plays loud music for a living, I don’t like loud music in any capacity. At home, I mainly use an old tube travel Magnavox Micromatic record player. It’s stereo, which is cool, but you’ve got to get the balance just right; you have to lean it more toward the left. I use that, or I have a small system that’s powered by Tom Dowd’s personal McIntosh MC240 tube amp, which I bought from his daughter. It’s the same one he used to mix Layla, Otis Blue, and every Allman Brothers record he worked on. It was the amp he carried around to Criteria Studios [in Miami] or here in New York. You’ve talked to him - he was such a nice guy, right? Rest in peace, Tom. [Legendary producer/engineer Tom Dowd passed away in 2002. He produced Bonamassa’s debut, 2000’s A New Day Yesterday.]

Most of the time, I sit in my guitar room, and I have my computer open. I have thousands of songs there. I have the second generation of the Bose Bluetooth [SoundLink] speakers - the first generation was shit. It sounded horrible, and once you went off the wire and went to the Bluetooth, you couldn’t get 5 seconds out of it. By and large, I’ve been very satisfied with Bose. I’m not a headphones person, but I do have the noise-canceling ones for the airplane. I call them my “screaming baby protectors.” (both laugh)

I sometimes walk around the city with my noise-cancelers on, without any music playing, just to cut the noise. New York is the loudest city in the world.

Yeah. It’s got to be, baseline, 95 dB.

And sometimes even louder than that. What are your favorite go-to records when you put on music?

I like Ray Charles’ Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music [1962]. The thing is, when I put on a CD, I know I’ve got 45 minutes to an hour to deal with it before it recycles or goes to the next thing. When it’s Vinyl Night, you only get about 15 or 20 minutes a side before you have to go pick up the needle.

For me, there isn’t a better experience than putting a record on and listening to music that was made direct to disc or with, at the most, 8 tracks. And I love early stereo records when there were no rules. Sometimes the drums and the bass were on one side, and the guitar was on the other. And the reverb return from the old EMT plate was on the left. That’s when you hear the bleed between the instruments and you hear a band playing in a studio live, you hear human beings and you hear out-of-tune instruments - and it’s all in the same room.

You used a word earlier that’s very important: clinical. To me, it all starts with the process. You can’t blame it all on digital. I’m not formally educated in music, but I informally educated myself on a 31-band graph. I took enough shit from monitor guys who would say, “I can’t help you”... no. That’s OK, I’ll help myself.

“As far as home stereo listening goes, I’m analog all the way.”

When I do a session in a studio and there’s a new assistant engineer - inevitably, if I see somebody under the age of 30, I get the same service. Everybody’s got their flashlight out, looking for where the middle of the cone is, to line it up. I ask them what they’re doing, and they say, “Well, that’s where the guitar amp sounds best.” I go, “Let me show you something. You know where the guitar amp sounds best? Right where you stand over the top of it.” Then they’ll say, “Well, we can’t have leakage into the drums.” “What, are we making drum samples, or are we making a record? I’m not going to be out of tune, don’t worry about it.” The problem is if you have absolutely no bleed and everything is fully separated, you get this very clinical, sterile-sounding record.

And you can’t be sterile for a record like Different Shades of Blue. We’ve gotta hear you and those horns interacting, you and Reese Wynans’ keyboards interacting, and hearing the character of the different tones you have, depending on the guitar you’re playing.

Yes, and the beauty of it is, it’s warts and all. You’ve gotta have the whole of it - the mistakes, the interactions, the snare drums that are buzzing. There are different processes for different styles of music. I just happen to have a very traditional view of it.

We share a lot of the same favorite records. I’m a John Mayall and the BluesBreakers guy like you are, and I totally love Layla. The sound on that album is as honest as it gets.

Oh yeah. You ever see that documentary, the one about The Wrecking Crew? It’s been leaked online. To make the movie right, it would require one billion dollars of sync licenses. (both laugh) Anyway, there are all these great stories of what was happening in the studio with Tommy Tedesco, Carol Kaye, and Hal Blaine. There were two bass players, two drummers, two of everybody, and live horns. They were chart-reading mofos, and the amps were live in the room. And that’s it. They’d walk into the session, they’d play, and three hours later, there’d be a whole record.

People always ask me how long I go into the studio - a month or two, or more? I go, “Nine days.” “Wow!” Listen, that’s still a long time in terms of the 1950s and ’60s. We do about two to three songs a day.

You don’t want to play the feel out of a song by the time you get to Take 10.

I think by Take 5, you’re out of it. Ultimately, what happens is you’re going for the intention, not the note perfection.

If songs like “Heartache Follows You Wherever I Go” or “I Gave Up Everything for You ’Cept the Blues,” were too “clean,” the listener wouldn’t feel half of it. It would be like lounge blues.

Yeah, it doesn’t work. It won’t work.

The vocal echo you use at the beginning and ending of “Oh Beautiful” gives it an extra dimension. Is that something that came up in the writing process?

No, it was something Kevin Shirley messed around with. We do the record hybrid. If there’s reverb on something, it’s not an EMT plate or a tape echo. Kevin [longtime Bonamassa producing partner Kevin Shirley] has a cool collection of early digital stuff that goes back to when I started recording - things like EMS spring reverbs. He’s also really adept with ProTools, where he can delay the reverb and create these kind of cool echoes. It all adds dimension that will challenge the listener. It can’t be so straightforward so that you know how the record is going to end, like a book or movie.

“For someone who plays loud music for a living, I don’t like loud music in any capacity.”

There’s a different mastering process today. And you can only go so low on vinyl. I do find that a lot of the older guys we grew up loving embrace the new technology: “Oh my God, you know how much easier it is now than it used to be?” I remember making mixdowns onto separate reels of tape, just so you could do overdubs. Then you’d take it back to the original tape, because you didn’t want to deteriorate your drums by going over it a billion times.

How has your vocal technique changed at age 37? Do you feel like you’ve come a long way as a singer?

When I was in my 20s in L.A., abusing myself with cigars and scotch and then wondering why I was losing my voice every night, my doctor, Joseph Sugarman, told me, “You’ve got to go learn how to sing.” He sent me to a guy named Ron Anderson, a wonderful vocal coach who taught me how to sing properly about 10 years ago.

I had an epiphany this year. According to my mother, I took a soccer ball to my face as a kid, and probably broke my nose and didn’t know it. So one side of my nose was almost completely collapsed. When I was doing the singing for this record, Dr. Sugarman told me to use a Breathe Right strip, and then let him know how it felt singing that way. It was unbelievable. So I had it fixed permanently, and had my deviated septum repaired.

Wow. Can you tell the difference when you’re singing now?

It’s the difference between a 4-cylinder and an 8-cylinder. Your head voice explodes, because you can breathe. It really was the key.

Does this influence how you do your setlists?

If you sing properly, it’s no more taxing than if you talk. You can blow out your voice in the first three songs, and you’re done. It’s now a lot less strenuous a show to sing. I don’t have to struggle through stuff on the record that used to be high to sing. I don’t sound so hoarse.

Is there an example of a song on Different Shades that you couldn’t have done before the surgery?

The title song, “Different Shades of Blue,” probably wouldn’t have happened in that key. It would have been moved down.

And that song is also a nice tone break before getting to the last three songs on the album.

Thanks. What’s your theory about a running order?

My view is, you the artist presented these 11 songs in a specific order to take me on some kind of journey, so I should honor that at least once.

Right! I tell people, “Look, do me a favor, listen to it in the order it’s intended.” It’s very easy to import an album into a computer and make it any order you want, and just mix and match records. Sequencing is a lost art.

“I love early stereo records when there were no rules.”

Today’s artists and producers understand that even their best fans may not make it to Track 11, so they’re gonna frontload the record with the best tunes, knowing that by Track 5, people are bored. The first five tracks or so are for radio and exposure, but to get to where the artist’s heart really lies, it’s probably there on Tracks 7, 8, 9, and 10. That said, I know my fans will listen to the whole record.

Did you like going out and buying records as a kid? Which ones influenced you the most?

I used to love going to the record store with my father. For the first two records I bought with my own money, we went to Camelot Music in Sangertown Mall in Utica, New York. I had 15 dollars saved up from mowing lawns and general manual labor around the house, and the tooth fairy provided the rest. At my age, the going rate for one primary tooth was a dollar. (laughs) The first record I bought was B.B. King

involved in.” By the time I got to the Introduction record, I was so inspired by how much work you have to do to get there. I was like, “Ah, I’m in! Let’s go!” Live at the Regal [1965], on my father’s recommendation - the one with the red cover, on vinyl. And my father bought a copy of Jethro Tull’s Stand Up [1969] -

“A New Day Yesterday” was on that album, and that’s where you got the name for your first album.

Yep! And I also bought a copy of Steve Morse’s The Introduction [1984]. Because I liked the fact that my father went, “He’s the guitarist with the Dixie Dregs, and he’s really good.”

The excitement you feel at the time of cracking that plastic open, and then you put that record on - all that anticipation, by the way, happens with the smooth part of the vinyl, the 2 seconds before the first song starts. When I heard, “Ladies and gentlemen, B.B. King” - I was sold. That sold me on vinyl, sold me on blues, sold me on B.B. King, sold me on, “I don’t care what I have to do, this is what I want to be."

And you’ve long since established your own voice as an artist. You said, “This is what I’m going to do - follow me or don’t, because I’m not following convention. I have a vision.”

And you’ve long since established your own voice as an artist. You said, “This is what I’m going to do - follow me or don’t, because I’m not following convention. I have a vision.”

Thank you. You can’t be anything you’re not. And I didn’t win a singing contest either. (smiles)

digitaltrends.com/music/blues-master-joe-bonamass-on-hi-res-recording-vinyl-and-more/